The dialectic between color and form has always inflected, even impelled the painting of Sigrid Burton. Sometimes color does seem to overwhelm form, but more often form asserts itself in the midst of her luminous, translucent clouds of color, giving unanticipated backbone to otherwise invertebrate masses of hue and tone. If color is the more omnipresent protagonist in Burton’s dialectic, form is the more persistent. And note the term “protagonist”, not “antagonist”: Burton’s color-form dialectic is a dialogue between partners, the senior partner the more prominent, but not the more important.

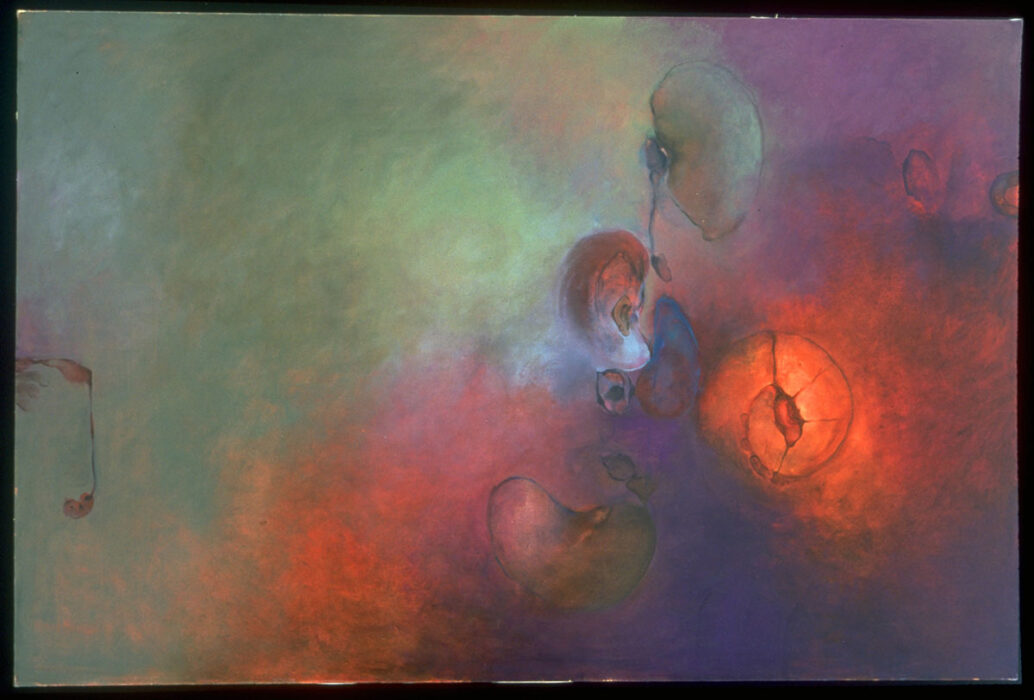

Never has this been more evident than in Burton’s recent series of canvases and works on paper. In these, her characteristic numinous color, darker and more brooding than ever, seems to gel in crucial places (normally towards the center of the canvas) into some sort of organic presence — more flora than fauna, but with a peculiar vitality, even sense of kinesis, as well as an equally peculiar relationship with the atmosphere(s) around it. This relationship is fraught with ambiguity: it balances on the breakdown of distinction between figure and ground (as well as between plant and animal), but resists the dissolution of that figure. Indeed, the figure, bulbous, tendrilous, unfurling, glowing — itself infused with Burton’ luminous hues — seems, if anything, to be drawing strength from its surroundings, like a lily pad absorbing nutrients from its pond.

The water-plant simile seems apt — rather more so than other associations readily provoked by these mysterious forms, forms rendered with such calculated, even calibrated inexactitude. While giving shape, focus, and, yes, local color to her pictures, Burton’s images themselves float in decidedly aqueous milieux. If they can be read as buds and leaves and flowers and stems, they still do not seem landbound (unless the immanent murk around them could be interpreted as the unvariegated mulch of a forest floor or bog — which, of course, would only mirror the flotsamic humor of sea and lake alike). Perhaps they are species of kelp, or perhaps tree branches that have fallen into a lagoon. Or, indeed, these delicate trails and bubbles may be marine animals, coelenterates or mollusks adrift in their element. Shell-like — and bladder-like, and fin-like, and tail-like — these shapes appear just often enough (and just enough of each appears) in Burton’s latest body of work to obscure the distinction between plant and animal. Are these beings, and being-fragments, in fact microscopic? Could they be diatoms or even microbes existing at a level where the discrete natural kingdoms converge?

Beyond this point, such conjecture leads away from the essence of Burton’s painting. It’s not that such a metaphorical inquest is inappropriate; the images are inarguably redolent of the natural world. But Burton is not praticing botany or microbiology here, she is practicing the even less exact art of present-day painting — less exact, that is, in terms of “recording” the exterior world, but arguably more exact in terms of reordering the world through the sensibility of the image-maker. She exploits the very inexactitude of representation that painting affords her, in order to afford us (and herself) the pleasure of the image and of the color that suffuses it. She also allows us the more ludic pleasure of trying various identities onto her forms; but of course it’s an open-ended game, never settling into a process by which the viewer’s attention diverts from her central concern, the presence of the painting as an entirety. The painting is at issue; the image at its core may be its spine, but it is not its subject. The subject here is the whole of the painted picture, formulated with oils on a rectangularly bounded canvas plane — and the impact that picture has on the eye of the beholder.

It is a pleasant diversion to “read” Sigrid Burton’s paintings for their real-world associations. It is far more appropriate, enduring and gratifying simply, and ultimately, to see them — to look at once at and into them, to comprehend those real-world associations, in all their ambiguity, as part of a concept of the visual that fuses the known with the unknown, the seen with the unseen, the associable with the ineffable — to the point where the ineffable is identifiable, as a meta-nature of the eye.